Wednesday, 24 August 2011

A little howse raised of mightie stones (John Norden, 1584)

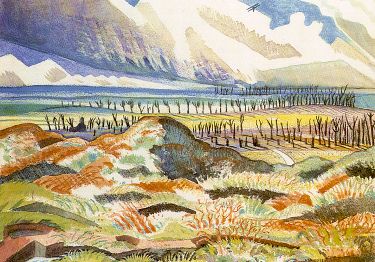

The early morning sun drew me away from my study and out again for a good three-hour walk along the fringes of the moor. Destination: Trethevy Quoit, near St Cleer, aiming to be back by 10.00 before the predicted heavy rain materialised. Success on all accounts! I’ve seen and marvelled at quoits in West Cornwall, particularly Zennor Quoit, near where the painters Bryan Wynter and Patrick Heron once lived and near where I had productive composing retreats in the 1980s. But Trethevy Quoit is something else.

It’s massive. It has crazy angles, a mysterious hole in the ‘roof‘ and a puzzling neolithic version of a cat-flap at the SE end. Shame about the unlovely houses next door. Even so, it’s spectacular. Whatever you think of the claims for its solar alignment, potential for astronomical observation and other speculations about its intended structure and usage, it remains an awesome monument to ancient endeavour and societal honour.

And there are great views. To the W: the tall tower of St Cleer parish church. From the N to the E: engine-house chimneys and other evidence of the copper-mining boom of the mid-late 19th century. Today, it’s quiet, apart from the excited twittering of a charm of goldfinches feasting on thistle seeds. Back then, Trethevy Quoit must have seemed a bizarre, silent relic beyond which all hell was breaking loose. No-one has quite caught the contrast between Trethevy Quoit and the South Caradon mine better than the author Wilkie Collins in this well-known passage from Rambles Beyond Railways: Notes in Cornwall Taken A-Foot (1851):

And there are great views. To the W: the tall tower of St Cleer parish church. From the N to the E: engine-house chimneys and other evidence of the copper-mining boom of the mid-late 19th century. Today, it’s quiet, apart from the excited twittering of a charm of goldfinches feasting on thistle seeds. Back then, Trethevy Quoit must have seemed a bizarre, silent relic beyond which all hell was breaking loose. No-one has quite caught the contrast between Trethevy Quoit and the South Caradon mine better than the author Wilkie Collins in this well-known passage from Rambles Beyond Railways: Notes in Cornwall Taken A-Foot (1851):

… about a mile and a half from St. Clare’s Well, we stopped to look at one of the most perfect and remarkable of ancient British monuments in Cornwall. It is called Trevethey Stone, and consists of six large upright slabs of granite, overlaid by a seventh, which covers them in the form of a rude, slanting roof. These slabs are so irregular in form as to look quite unhewn. They all vary in size and thickness. The whole structure rises to a height, probably, of fourteen feet; and, standing as it does on elevated ground, in a barren country, with no stones of a similar kind erected near it, presents an appearance of rugged grandeur and aboriginal simplicity, which renders it an impressive, almost startling object to look on. Antiquaries have discovered that its name signifies The Place of Graves; and have discovered no more. No inscription appears on it; the date of its erection is lost in the darkest of the dark periods of English history.

Our path had been gradually rising all the way from St. Clare’s Well; and, when we left Trevethey Stone, we still continued to ascend, proceeding along the tram-way leading to the Caraton Mine. Soon the scene presented another abrupt and extraordinary change. We had been walking hitherto amid almost invariable silence and solitude; but now, with each succeeding minute, strange, mingled, unintermitting noises began to grow louder and louder around us. We followed a sharp curve in the tram-way, and immediately found ourselves saluted by an entirely new prospect, and surrounded by an utterly bewildering noise. All about us monstrous wheels were turning slowly; machinery was clanking and groaning in the hoarsest discords; invisible waters were pouring onwards with a rushing sound; high above our heads, on skeleton platforms, iron chairs clattered fast and fiercely over iron pulleys, and huge steam pumps puffed and gasped, and slowly raised and depressed their heavy black beams of wood. Far beneath the embankment on which we stood, men, women, and children were breaking and washing ore in a perfect marsh of copper-coloured mud and copper-coloured water. We had penetrated to the very centre of the noise, the bustle, and the population on the surface of a great mine.

Here’s a more recent response to the ‘startling object’. It’s by Charles Causley, born this day in 1917, in his poem ‘Trethevy Quoit’ (Field of Vision, 1988):

Here’s a more recent response to the ‘startling object’. It’s by Charles Causley, born this day in 1917, in his poem ‘Trethevy Quoit’ (Field of Vision, 1988):

Sea to the north, the south.

At the moor’s crown

Thin field, hard-won, turns on

The puzzle of stones.

Lying in dreamtime here

Knees dragged to chin,

With dagger, food and drink –

Who was that one?

None shall know, says bully blackbird.

None.

Field threaded with flowers

Cools in lost sun.

Under furze bank, yarrow

Sinks the drowned mine.

By spoil dump and bothy

Down the moor spine

Hear long-vanished voices

Falling again.

Now they are all gone, says bully blackbird.

All gone.

Hedgebirds loose on wild air

Their dole of song.

From churchtown the tractor

Stammers. Is dumb.

In the wilderness house

Of granite, thorn,

Ask where are those who came.

Ask why we come.

Home, says bully blackbird.

Where is home?